Interviewer: Jeff Tamarkin

Other notes: Luis Raul Montell

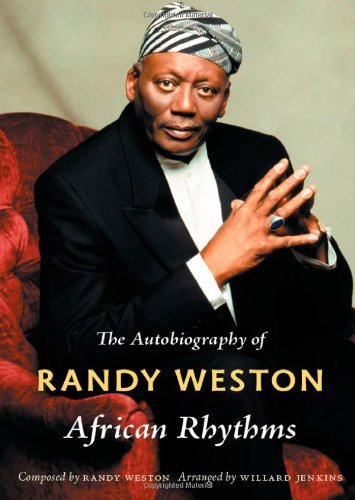

Next April 6 this year the NEA Jazz Master Randy Weston will be celebrating 90 years, the always been praised to publicize, explain and interpret traditional African music mixed with jazz. It was very important their dedication in this musical range as well as it has been for the various subgenres that to make the Latin Jazz. Earlier this year, as every year occur in January, I was held the Panama Jazz Festival and it was dedicated tribute to Mr. Weston.

His presence was a major event and then answered the following questions:

What first drew you to African music?

R.W: My dad said that Africa is the first civilization on the planet. All civilizations come out of Africa. We are African people in the Americas and we have to study the history of the African civilizations. The whole human race comes from Africa. Everybody on the planet’s got African blood. It’s a big secret, but once that comes out we might be a little better. We’re all related to each other. All you’re gonna get about Africa [in the schools] is colonialism and slavery; up until today, it’s still the same thing. My dad had me read about ancient civilizations when I was a kid; he kept books in the house. And he made me take piano lessons. He was the key; he was the guy.

Do you feel like you’re still learning more about African music?

R.W: Of course. It’s not just the music but the continent itself. It’s so diverse and so rich and so complicated. You never really learn Africa; you just take what you can. I was hanging out with traditional people there, seeing how they view the importance of music. We tend to think that music began in Europe but Africa has had great music for thousands of years. The Egyptians had schools of music. You realize how little you know.

When you were growing up in Brooklyn and first listening to jazz, did you know that it had roots in Africa?

R.W.: No, I didn’t know. My father gave me the background and told me to study and read so I was more interested in history and architecture and science. But it wasn’t until I met some traditional African musicians and they played some traditional African music for me, and then I collected traditional African music, that I realized, of course. We were taken away but America’s 400 years are nothing compared to Africa itself. Our ancestors brought this music with them. People like Louis Armstrong approached life as Africans. When you hear the traditional way of life, you can understand why.

How did you get into jazz?

R.W.: I was lucky. I had great teachers. Marshall Stearns was the first jazz scholar and he had these classes up in the Berkshires, in the ’50s. I was lucky to be there. He was a white professor at Harvard but he had a pan-African concept. He would invite people like Mahalia Jackson, John Lee Hooker, Dizzy Gillespie. He would describe African culture, and wherever African people were taken they would create music based on what’s available.

As you travel around, do you find that people understand the connection?

R.W.: It’s not in the educational system, not in the cinema. So people can’t understand. I do a lot of schools and talk to these kids; they are so happy. I said, “The whole human race began in Africa. That’s yours too.” Then I explained how, with traditional people, music started by being in touch with the universe, listening to the rhythms of the bees and the birds and the sound of thunder. Mother nature was the original orchestra. Music was started in Africa by people who knew the language of the birds and the animals. It’s so important because it gives a better appreciation of this music that we all love.

It’s not just jazz either—it’s R&B, rock and roll, rap.

R.W.: Everything. America is also an African country. We grew up with segregation and we couldn’t go out but people would come in. We had the black church on Sunday and we’d do the calypso dances, listen to the blues groups. All kinds of music was ours.

Is it getting better? Are people more aware now?

R.W.: It can’t get better until the media gets better. We’re completely backwards. I remember the good old days of [TV hosts] Steve Allen and Jackie Gleason and Dave Garroway. They’d have jazz on their shows all the time. But there’s absolutely nothing for young people to learn today. It’s very bad, because this is America’s classical music. That’s why it’s so tragic. This music is popular all over the world.

Why did you choose the piano? It’s not associated with Africa.

R.W.: I didn’t choose it—my father chose it! He was a very strong guy! He was from Panama and said he heard a pianist in Panama at a hotel and he loved the music. So Pop decided he wanted his son to be a piano player. I was very tall for my age—six feet when I was 12 years old—and I wanted to play basketball and football. Pop said, “No, you practice that piano.”

Who was your biggest piano influence?

R.W.: I learned from all of them. I learned from Willie “The Lion” Smith. I used to go to Eubie Blake’s house; he lived in Brooklyn. Nat “King” Cole for his beauty. Count Basie for his space. Mr. Art Tatum, the giant of all. And Monk and Duke Ellington. I discovered Duke Ellington last because I always thought of him with the orchestra. But I heard him do a trio set and it was so beautiful I discovered Ellington the pianist. I would say Ellington and Monk made the biggest impact.

Is there anyone coming up today who you like?

R.W.: A lot of young musicians. Rodney Kendrick is good. This young Cuban pianist, Elio Villafranca. But that period we grew up in, that’s our royalty. They took the piano and did something that nobody else did before.

You’ve been playing with your band, Randy Weston’s African Rhythms [Weston, piano; TK Blue, alto saxophone and flute; Billy Harper, tenor saxophone; Alex Blake, bass; Neil Clarke, African percussion] for a long time. Tell me about them.

R.W.: I met Alex when he was 16 years old, in the ’70s, playing with Dizzy. The first time I heard him he played just like plays today. He is so rhythmic and so original. Neil Clarke spent years with Belafonte. He’s a teacher. And then we have Billy Harper and TK Blue.

Tell me about your ongoing residency at the New School in New York.

R.W.: It’s wonderful. I got a call and they said, “Randy Weston, we’d like you to be the first artist resident, but what would you like to do?” I said, “I’d like to bring Africa.” I’ve always had that curiosity: What’s the beginning of language? What’s the beginning of slavery? I said, “I’d like to bring over traditional people. And have them not just perform but explain the complexities of traditional music and how well it’s organized and how spiritual it is, and how they are healers and storytellers.” They do dance and music and play games. They wanted to have my life in music, talking about living in Africa and telling people about my experiences.

You’ll be 90 in April and you still perform. What’s left for you to do?

R.W.: I’m still learning and reading. I was with the Africans in Brazil. Then you’ve got the ones in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and wherever they are, they have different rhythms. The pulse is always there. We spent 10 days down in Mississippi and went to Robert Johnson’s grave. I’ll always be a baby with this music. With Africa, you keep learning about music and learning about Africa.

When people look back in a hundred years, what will they say about Randy Weston?

R.W.: I think my contribution is recognizing that great people were taken from Africa and gave us so much spirituality and love in the world, despite their condition and their pain. My mother and father had a hard time. Your color was no good, your hair was no good, you couldn’t get work, but they never complained. And they were spiritual. So I went to Africa because the African people, they give. You go to the smallest village, the guy will give you his bed to sleep in. If they have a loaf of bread, you’ve got to share that loaf of bread. My mother and father were the same way; they were always giving. Dizzy and Duke, all those people were always giving.

Mr. Weston has more than fifty (50) Albums recorded, Throughout his career as continuous talks, master classes of music, concerts around the world.

"Randy Weston trace the path of African Jazz" - Luis Raul Montell

Mr. Weston has more than fifty (50) Albums recorded, Throughout his career as continuous talks, master classes of music, concerts around the world.

"Randy Weston trace the path of African Jazz" - Luis Raul Montell

In the video we will see below, which occurred on stage at the Panama Jazz Fest 2016, we can appreciate the genius of impromptu execution African Jazz by Randy Weston and his guests the moment:

¡¡Viva The Latin Jazz!!

www.jazzcaribe.blogspot.com jazzcaribe@hotmail.com

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario